Timber or wood has been used in construction for thousands of years and next to stone has arguably been used to construct most dwellings and other buildings, boats and other modes of transport, weapons and furnishings across the ages.

There are hundreds of different types of timber due to the vast range of trees and environmental conditions that shape them, but not all are entirely suitable for use in construction due to factors such as cost, ease of use, sustainability etc.

In terms of what different types of timber there are, on a basic level there are essentially two types – hardwoods and softwoods, but underneath each of these top level types lies a huge range of slight variations, each with their own unique characteristics.

Pine forrest

Why are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Timber Used in Building?

One of the biggest reasons that timber is so widely used is, due to it being a natural resource, it’s available pretty much everywhere and it’s sustainable.

In respect to sustainability, timber is the gold star, top of the class material, above and beyond pretty much all other materials used in the building trade.

It’s main gold star characteristic is the fact that it’s renewable (can be grown again), biodegrades (rots down and requires no intensive carbon-producing process to manufacturer it, quite the opposite in fact, and through this has virtually no carbon footprint.

Timber can also be machined and cut to a huge variety of shapes, lengths and sizes and, for its weight, is very strong.

With all of these up sides you may be thinking – why don’t we just build everything out of timber?

A good question indeed – For all of it’s vast range of advantages, timber does however have a few disadvantages in that its strength has limitations.

If you were to build a skyscraper from timber, the size of the timbers at the base to support all of the weight above it would be massive in comparison to any steels used in their place.

Although sustainable timber can be grown in as little as 5 years, that’s still a fairly long time when you consider that steel and concrete can be manufactured and processed in as little as a single day.

As you may be all too familiar with if you have timber frame windows, external doors or other items that are exposed to the elements, if timber is not treated to resist the effects water and moisture it will rot and degrade.

On the whole, any disadvantages that timber may have is far outweighed by its advantages.

Sustainability and Environmental Impact

Environmental awareness and deforestation are two huge subjects worldwide at present and are likely to be high on the social awareness list for many years to come.

With this in mind, whether you’re a large building firm or smaller sole trader you will need to exercise some responsibility in terms of where they obtain your materials, especially timber and ensure that any that’s used comes from a sustainable source.

Large scale tropical deforestation

This isn’t just an “ideal world” scenario, it really does have to happen to ensure that we actually have a planet for not only us to live on, but also our children and our children’s children!

With all the timber that’s actually for sale across all the DIY sheds and builders merchants in the UK, you may be wondering how you can actually tell if it’s come from a sustainable source?

On the 3rd of March 2013, the EU put in place measures to regulate the sale of timber and counter act illegal logging trade by introducing the EU Timber Regulation (part of their FLEGT Action Plan).

The goal of this particular regulation is to ensure that no illegally sourced timber or timber products can be sold in EU (European Union).

Part of the legislation is there to make sure that any European-based timber producers operate a sustainable business and any trees that are harvested are indeed replaced. This has essentially meant that forests across Europe have actually increased, all very good news.

With the above in mind, you should only use timber produced within theEU, this way you can be pretty much sure that it has come from a sustainable source.

As for timber sourced elsewhere such as South America, Asia and the US, the rules are a lot less strict in these countries therefore meaning that chances the timber has been illegally sourced is much higher.

As good as rules and regulations are, as I’m sure you know by now you can never 100% guarantee that everyone follows them and even timber sourced from some EU-based countries can be questionable, therefore there are some further checks that need to be made.

In terms of this, you should always look for timber suppliers and timber that’s been certified by the FSC (The Forest Stewardship Council) and also the PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forestry Certification).

Part of the certification and enrolment process for both organizations ensures that any suppliers operate a sustainable timber supply business.

The Forest Stewardship Council

Programme for the Endorsement of Forestry Certification

What is CLS Timber?

If you have been involved in any form of building or DIY, no doubt you have heard the term “CLS”. In terms of what it stands for, CLS stands for “Canadian Lumber Standard”.

As you may have guessed from the name, it originated in Canada and is typically used to describe the 3×2 inch or 4×2 inch etc. timbers used to constructed timber framed houses and internal stud work.

CLS timbers themselves are, in most cases, planed on all four sides, with each edge also being slightly beveled.

Piece of CLS 3×2 inch timber

Most DIY sheds and builders merchants will supply CLS in the following sizes in both C16 and C24 grades (more on this below):

- 50mm x 75mm (3 inch x 2 inch)

- 50mm x 85mm (3.5 inch x 2 inch)

- 50mm x 100mm (4 inch x 2 inch)

- 50mm x 150mm (6 inch x 2 inch)

In terms of lengths, the standard supply lengths of CLS timbers are normally 2.4m long and 4.8m long.

How is Timber Graded?

In the same way that you may have heard theterm CLS, you may have also heard some timbers referred to as C16, C24, D30 etc.

In the same way that you may have wondered what CLS stands for and how it relates to a given timber you may have also wondered what this terminology also means.

In essence, C16, C24, D24 and all other “C” and “D” permeations are to do with the strength of a given timber as defined by the European Standard EM14081 (also see updated version EN14081-2 here) and through its strength, this then determines where and what it can be used for.

On a very basic level, the lower the “C” number the weaker the timber is (e.g. C16) and the higher the “D” number, the stronger the timber is (e.g. D30).

Timber grading stamp – Image courtesy of woodcampus.co.uk

The process of grading timber is quite a complicated one and uses several different methods and sets of rules with the goal of sorting different timbers with different properties into groups to identify how strong they are and how they’ve been processed.

The three main grading processes are:

- Stress grading by machine: Traditionally timbers are graded through small stresses being applied to them by small weights, much less than their total design strength over their minor axis (e.g. on a flat edge) by a machine and then stamped with their grade, ID number, who’s produced them and what condition their in

- Stress proofing by machine: Similar process to stress grading above only this time high load stresses are applied via large weights, close to the total design strength of the timber to the major axis of the timber (e.g. on an edge)

- Visual stress grading: As it sounds, timbers are visually tested by a visual grading expert according to a set of visual grade testing rules. The rules concentrate on the naturally occurring defects in timbers such as sizes and locations of knots and other imperfections that reduce the overall strength of a given timber

Typically when stress grading timbers via a machine, both checks are used, firstly to remove any weak timbers and secondly to ensure that the timbers that passed the first test are fully up to strength.

As you may be thinking, pushing something to its absolute limits could overstress it and by thinking this you’re right. It’s thought that a small percentage of the timbers that do actually pass these tests are pushed so far that it does actually effect their performance over time.

Machine testing and grading timbers is quite a lengthy and costly process so more modern techniques have been developed to speed up this process. These involve x-ray testing and also acoustic vibration testing.

As mentioned, both machine and visual grading processes are fairly complex and involved so the above information serves only as a brief overview of what’s involved.

One point to note in terms of graded timbers in the UK is that as most homegrown UK timber tends to be fast grown it can’t obtain a grade of anything higher than C16.

Timber strength grading machine – Image courtesy of napier.ac.uk

Aside from grading using the methods outlined above there are two further classification methods to be aware of and these are kiln dried timber and unseasoned timber.

Any graded timbers have generally been kiln dried. As well as testing a given timber for it’s strength, it’s moisture content is also tested and to reduce moisture levels to that required by a particular grade, the timber is dried out in a kiln until the desired moisture level is reached.

The other final classification is unseasoned timber. This is pretty much raw-grade timber cut straight from the source e.g. cut from a log in a saw mill.

As unseasoned timber is cut directly from the raw material it’s what’s known as “rough sawn” e.g. it’s not planed or finished and as there is no finishing, dimensions of individual lumbers can vary slightly.

Additionally as unseasoned timber isn’t dried, moisture content can vary between individual timbers meaning shrinkage can vary.

Due to the above, unseasoned timber is not used for structural work and is mainly used in out door projects such as fencing and the similar.

To help prolong the life of both unseasoned, graded and other timbers they are put through a pressure treating process.

As opposed to preservatives simply being applied to the outside of a given timber in a similar manner you would apply fence treatment to a fence, the preservative is forced directly into the timber making it much more resistant to water damage, decay, wood boring insects and other typical vulnerabilities that timber traditionally has.

Pressure treated timbers are on the whole more expensive than their non-treated counterparts, but to guarantee the longevity of any given job, it’s well worth the extra expense.

What Different Types of Timber are There?

As we have now established why timber is used in construction, what’s it’s advantages and disadvantages are, how it’s tested and graded and how we can be more environmentally conscious when using timber in construction, it’s now time to actually look at the two main types of timber, namely hardwoods and softwoods.

There is often a little confusion around the terms hardwood and softwood and how each is used to describe and classify a given type of timber.

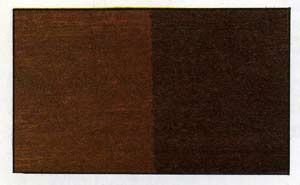

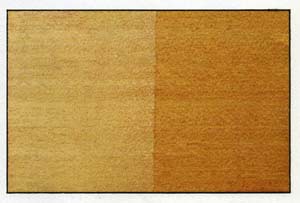

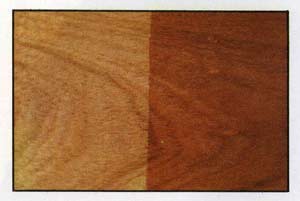

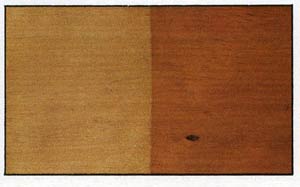

Comparison of hardwood and softwood together – Image courtesy of barbequescience.com

As the name may suggest, softwood timber is not necessarily softer than hardwood timber across the board as there is a great variation in the physical “toughness” of both hardwoods and softwoods, with some softwoods actually being harder than some hardwoods.

So, if some hardwood is softer then softwood and some softwood harder than hardwood, why are they classified this way? Well, it really has to do with their reproductive process and physiology.

In most cases, softwood trees are grown from cones e.g. pine trees from pine cones (in some cases can also grow from nuts) and have spiky leaves (needles) and are coniferous meaning they retain their needles all year round (Larch is an exception, and deciduous) with branches forming in whorls (rings). Several branches can also appear at the same level on the trees trunk.

When it comes to hardwood trees, these are mostly deciduous e.g. they loose their broad and flat leaves in autumn and then regrow them in spring for the summer months. Their seeds are also surrounded by a protective enclosure that can be hard such as a nut or soft such as an apple.

Now that we understand a little more about what the terms hardwood and softwood actually mean, lets look at the types of trees in each category and what their used for.

Types of Softwood

When talking about softwoods, many people refer to Deal, Pine and Fir. Pine and Fir are indeed species of tree, but Deal is a technical term (now obsolete) for describing a size of softwood, or its origin.

In general, softwoods are used to make non-load bearing structures such as internal studwork, doors, window frames, pulp for paper making and also particle board and fiberboard.

The softwood most commonly used in the UK is from the tree Pinus Sylvestris and is known as Redwood. Other names include:

- Red Deal

- Yellow Deal

- Archangel Fir

- Swedish Pine

- Scots Pine

The above are all common names used to describe essentially the same tree but there are quite a few other tree species classified as softwood, some of these are as follows:

- Cedar

- Western Red

- Douglas Fir

- Hemlock

- Parana Pine

- Pitch Pine

- Quebec Yellow Pine

- Western White Pine

- Sitka

- Spruce

- Larch

- Yew

- Silver Fir

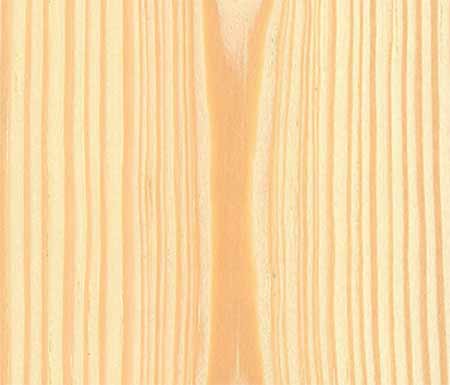

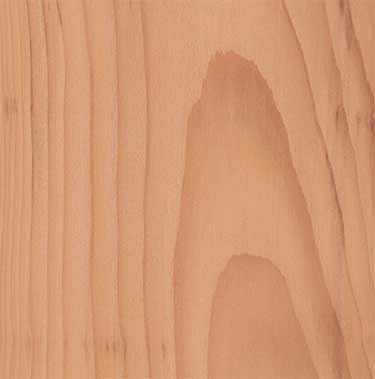

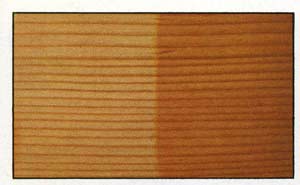

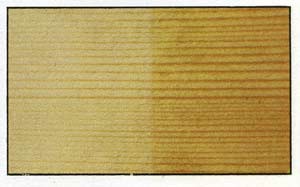

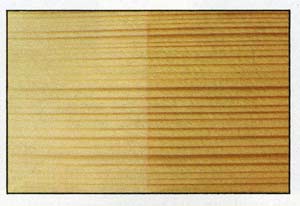

To get a good idea of how each looks visually, here are some examples:

Scots pine or Pinus Sylvestris

Western red

Douglas fir

Spruce

Larch

Yew

Silver fir

Types of Hardwood

Hardwood trees (or angiosperms as they are also known) have broad, flat leaves and are deciduous (Yew and Holly being exceptions). Branches usually grow at different levels and never more than two at the same level.

Hardwoods are generally used for more load bearing, heavy structural duties such as walls, floors and ceilings, but due to their often appealing visual appearances are also often used for furniture, veneers and cabinet making.

Quite often, hardwoods are also classified as being temperate e.g. from a seasonal climate where they shed leaves during autumn and winter or tropical e.g. from a tropical climate where temperatures/conditions are fairly consistent year round meaning they only occasionally shed leaves.

Unlike softwoods which are specifically grown and forested, most hardwoods, especially tropical ones, occur at random and are naturally growing. This makes felling and collection difficult raising the prices considerably against softwood.

This fact, and of course diminishing stocks, have led to greater interest in lesser known hardwoods such as Utile.

Other hardwoods commonly available in the UK include:

- home grown or European English Oak

- Beech

- Ash

- Elm

- Sycamore

- Birch

- Walnut

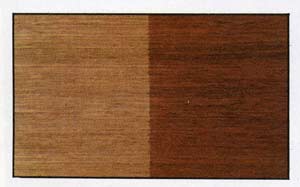

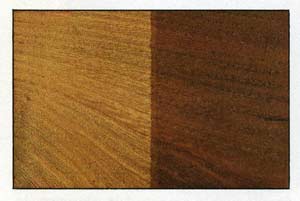

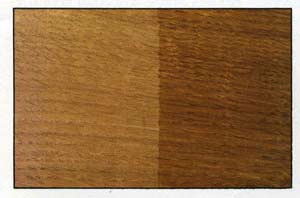

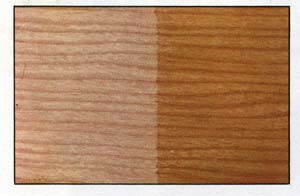

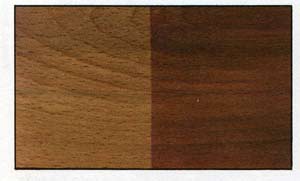

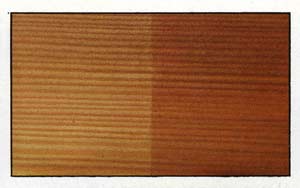

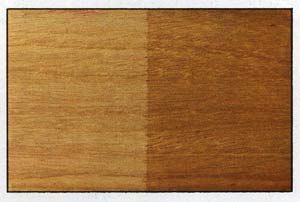

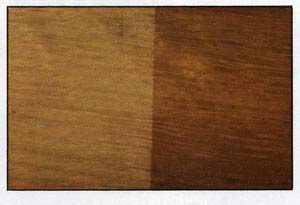

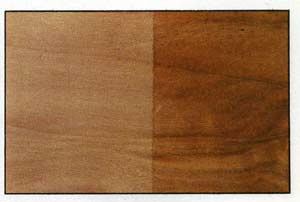

Because many of these woods have superb decorative value, they are often cut into thin veneers and used to face less expensive timbers. The images below may not be exactly the same colours as the original timbers, but give a good ide:.

African Mohogany

African Walnut

African WhiteWood

Afrormosia

Agba

Austrailian Oak

Douglas Fir

Elm

English Oak

European Ash

European Beech

European Larch

European Redwood

European Whitewood

Idigbo

Iroko

Jelutong

Kempas

Parana Pine

Poplar

As you can see from the above, hardwoods and softwoods can vary quite drastically in terms of characteristics and uses in some respects, but in others the differences can be fairly minimal.

With this in mind, it’s important that you select the correct type of timber for the job you are doing and also equally as importantly, ensure its come from a sustainable source.