There are generally 2 types of electrical circuit you may find in your home, the radial circuit and the ring circuit. Each type has its own specific uses and advantages.

In this guide we look at the radial circuit and how this is generally used in the home including how it’s wired up. For information on ring circuits, see our project here.

Staying Safe With Electricity

Electricity is dangerous, we all know this and are taught from a young age to treat it with care and respect. Despite the obvious dangers, if you are competent and understand how to work with electricity safely, it is more than possible for you to add your own circuits, including radial circuits.

In order to work with electricity safely you must understand how to correctly isolate circuits to prevent injury while you’re working, how to test your work to ensure it’s safe and there are no faults, ensure that you have used the correct components of the correct size or rating and that you are aware of any relevant rules and regulations.

For more information on working safely with electricity, please see these projects:

If you are not sure on how to isolate circuits correctly or test your work then please do not attempt any electrical work yourself, get the professionals in!

In order to safely isolate a circuit to work on it you must either turn off the circuit using the correct MCB in your consumer unit or pull out the fuse for the circuit if you have a fuse box.

To ensure no one accidentally turns it on, place a note on the consumer unit or fuse box informing everyone why it’s turned off.

If after reading the above you are confident that you tick all boxes as far as safety and competency go, then please read on and find out all about radial circuits and how they work.

What is a Radial Circuit?

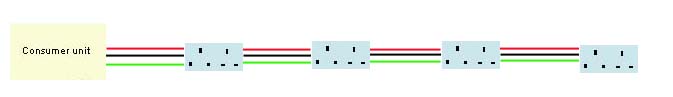

A radial circuit is a linear mains power circuit found in all homes to feed sockets, lighting points and other specific items like showers, cookers, boilers or immersion heaters etc. It is simply a length of appropriately rated cable feeding one power point then on to the next, if there are any. The circuit terminates with the last point on it. It does not return to the consumer unit or fuse box as does the more popular circuit, the ring main.

To explain a little further using sockets as an example, a radial circuit runs from the consumer unit or fuse box out to one or more sockets that are connected in a line, with each subsequent socket being supplied with power by the one before it.

The cable running from the power source (consumer unit etc.), runs to the first socket, where each wire (live, neutral, earth) is connected to the corresponding terminals on the back if socket face-plate e.g. live to live (L), neutral to neutral (N), earth to earth (E).

The second socket in the run is connected to the first socket using a length of cable that’s connected into the terminals of the first socket, so there are 2 sets of wires in each live, neutral and earth terminal. The other end of the cable is then connected to the terminals of the second socket face plate.

This pattern is then repeated for any further sockets until the end of the run is reached where it then terminates, so the last socket in the run will only have one set of wires connected to its terminals.

Along with the socket-based radial circuit setup above there are others that include the cooker circuit that is also a radial as is an electric shower circuit, immersion heater and the similar.

Although the same type of circuit in principle, these more specialist circuits have very specific requirement and so are subject to much more stringent regulations, and should only be attempted by the pro’s.

Lighting circuits are also radial circuits as they start at the consumer unit or power source and terminate at the final lighting point on the run.

One final point to make concerns fault finding. With basic circuits of this type, tracing faults is comparatively easy due to the fact that it’s linear.

Using sockets as the example, as each socket in the chain is powered by the one before, in most cases, all you have to do is find the point in the chain where the sockets stop working and the fault should reside with the unit just before that.

If none of the sockets are working, any faults should then likely reside with the consumer unit or power source.

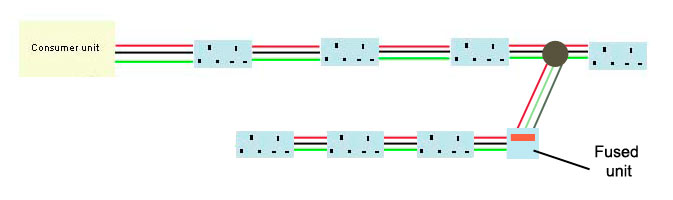

Diagram of a simple radial circuit

Advantages and Disadvantages of a Radial Circuit?

Radial circuits have numerous advantages and disadvantages, here are a few of each:

Radial Circuit Advantages

- Easy to wire up and run cables for

- Easy to trace faults in the circuit

- Can be cheaper to wire up radial circuits

- Low maintenance

- Uses less cable

Radial Circuit Disadvantages

- Radial circuits with many sockets might not be suitable for appliances that draw huge loads

- May not posses the same current carrying capacity as a ring circuit

- Can suffer voltage drop

- Easier to overload the circuit by plugging in lots of high demand appliances

- If high voltage items are connected up, appliances plugged in down the chain can suffer voltage drop

How Many Sockets Can I Have on a Radial Circuit?

In principle, you can add as many sockets to a radial circuit as you like, but in reality there are some caveats to this.

If you adhere to the principles above e.g. a radial circuit running from a consumer unit with its own MCB of the correct rating you can have as many socket as you like, as long as it’s in an area not exceeding 50 square metres (or 540sq ft).

That said, you will also need to consider what is likely to be plugged in to the circuit.

If it’s a pretty standard domestic setup such as a 16amp MCB, 2.5mm cable with 15 sockets, but you want to plug in and run 10 tumble driers all at the same time, then the draw on the circuit as a whole will be far too much for the MCB and it will trip straight away.

However, if you are only wanting to run a TV, charge some phones, power a router and a few other standard items then chances are you will have no issues at all.

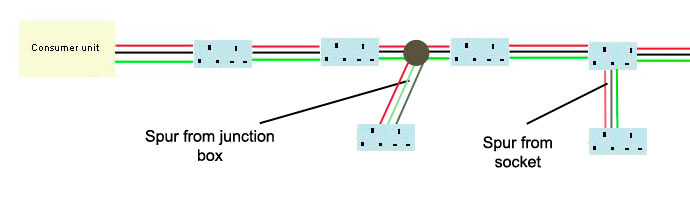

One other point to consider is if you are creating a new sub-circuit from an existing radial circuit, even though this will also be a linear circuit, it is technically not a radial circuit, it’s known as a spur.

A spur is similar in concept to a radial circuit in that a power feed is taken from an existing socket out to a new socket, but if this is done from an existing radial circuit then technically it’s a radial circuit running off a radial circuit so some additional rules apply (more about spurs can be found in our project here).

A radial circuit in it’s own right emanates from a consumer unit or power source, where as a spur is a branch off of an existing circuit, radial or otherwise.

With this in mind, a spur should only feature one additional new socket or appliance, unless it is preceded by a fused connection unit (FCU), in which case it can again feature as many sockets as you like providing the draw on the circuit does not exceed that of the fuse in the fused connection unit.

Also, the secondary fuse in the FCU should never be more than the original rating of the MCB or fuse that it’s connected to in the consumer unit or fuse box. For example the fuse in an FCU running on a 16amp radial circuit is 13amps, which it normally is, then this is fine. However if a fuse over 16amps is used then this is not acceptable at all and again, it should also not exceed the 50sqm rule stated above.

What Size Cable for a Radial Circuit?

The size of cable that’s used for a radial circuit will depend on the size of MCB it’s connected to and also what appliances are going to be powered from it. If it’s a lighting circuit then 1 or 1.5mm cable, if standard sockets then 2.5mm cable but for high demand appliances you’ll have to calculate the correct size.

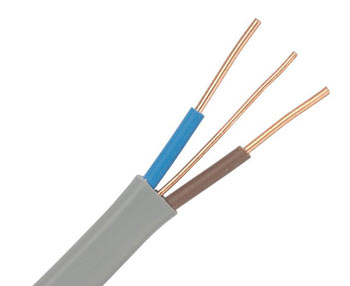

If you have ever done any basic electrics, you will be aware of the various different types and sizes of cables and these include twin and earth (flat cable) or flex (or flexible cable) which are the most common and all come in various sizes which should be selected appropriately for their intended purpose. More information on the different types and sizes of cable can be found in our cable sizes project here.

As we are mostly focusing on sockets, the most appropriate cable to use is 2.5mm twin and earth, or 2.5mm 2 core and earth as it’s also known.

2.5mm twin core and earth wiring for use with socket wiring

In pretty much all domestic situations, 2.5mm twin and earth is the cable to go for, for sockets circuits, the actual size of cable to use will be dictated by the size of MCB in the consumer unit and the appliance(s) that will be run from the circuit.

For a radial socket circuit, the size of MCB used should be no more than 16 amps. This will ensure that if the circuit is overloaded, the breaker will trip before the wiring itself gets so hot, melts and possibly catches fire. This will be more than enough for domestic appliances such as TV’s computers and washing machines.

For any more heavy duty appliances, such as a cooker, a more substantial cable is required. The size of wire and MCB breaker that’s used will very much depend on the rating of the appliance that’s going to be connected to it, so this will need checking first.

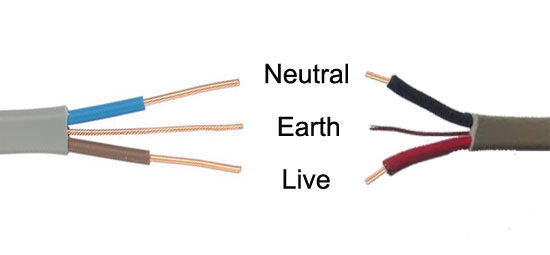

One final point to mention when it comes to wiring is the colours of the internal cores. Before March 2004 and the introduction of amendment 2 to British Standards BS 7671, standard wire colours were red for live, black for neutral and green and yellow for earth (or bare copper with a green and yellow sleeve).

After March 2004, wire colours became “harmonised” e.g. changed to the same colours as the rest or Europe, as this is as follows:

- Live = Brown

- Neutral = Blue

- Earth = Green and Yellow

With the above in mind, be aware that wires of different colours may be present so take note of these colours and what they represent. For more information on this, please also see our project on the New Wiring and Cable Colours.

Comparison of old wire colours to new wire colours

The Importance of Using Correct Sized Cables and Breakers

We have already touched on this point, but it’s an important one, so it’s well worth going over once more in it’s own right.

When it comes to maintaining the safe operation of an electrical circuit, having the correct size of cable protected by the correct breaker/MCB or fuse is essential.

To prevent injury and the possibility of fire due to overheating, the correct size of MCB should be used so that it trips the second a fault is present on the circuit or the overall draw of power across the circuit is greater than it is built to allow and in turn, too great for the size of cable or wire used.

In the sections above, we used the example of plugging in 10 tumble driers on a radial circuit formed from 2.5mm twin and earth. As a tumble drier requires a large amount of current to run, with 10 of them all trying to draw the amount of power they need from such a small gauge of cable, causes the cable itself to heat up.

If this load or draw of current is not stopped (by the MCB tripping or protective fuse blowing), the cable will continue to heat up to the point that it’s plastic outer sheath melts and then catches fire to any flammable items around it.

So, as you can see, using the correct size of cable and MCB is of the utmost importance.

Old electrical wire catching fire – Image courtesy of TED Systems

Can You Have a 32amp Radial Circuit?

In short, yes you can have a 32amp radial circuit, the supply to most cookers is a radial circuit as it serves only that single appliance and doesn’t run back to the consumer unit and as cookers draw huge amounts of power, it requires a 32amp breaker, but having said this there are other factors to consider, the most important of these being the size of cable used.

If running a radial circuit to supply a series of sockets then you would use 2.5mm twin and earth cable and a 20amp breaker as the power drawn through the circuit would likely not exceed 20amp and 2.5 twin and earth can cope with this draw.

However if you used the same cable on a cooker drawing up to and over 30amps then this would over heat it and potentially cause it to catch fire! So, as you can see, using the correct size cable for the size of breaker and appliance it’s supplying is extremely important.

Can I add Sockets to a Radial Circuit?

Yes you can indeed add additional sockets to a radial circuit, this is known as a spur. However you can only add 1 unless you use an FCU (fused connection unit) before it, in which case you can then add more than 1 socket. You will also have to ensure you use the correct sized cable and fuse in the FCU.

One additional rule is that your new spur must not exceed more than 50 square metres.

Single spur taken off of an existing radial circuit

Spur taken off of radial circuit with multiple sockets using a fused unit

In terms of where the spur can actually be taken from, this can be directly from an existing socket or by adding a junction box and wiring your spur from that.

How to Wire a Radial Circuit

Now that you know what a radial circuit is and how they work, it’s time to look at how they are installed.

In this scenario, we will be running a length of 2.5mm twin and earth from an MCB in the consumer unit out via a radial circuit containing 5 x 2-gang (double) sockets to small garage conversion which will be used as an office.

Note: Only qualified electricians are allowed to perform work on a consumer unit so in this instance the work will be carried out by one of our electricians. However, the principles of how the radial circuit is installed beyond the MCB can be applied to situations where they can be installed on a DIY basis.

Step 1 – Install MCB

Firstly, an MCB of the correct size is installed in the consumer unit. In this case a 16amp MCB is used as the items to be used in the garage-come-office are going to be relatively low powered e.g. a TV, some computer monitors, laptop etc.

The MCB is wired up correctly with the outgoing live connected to the live out of the MCB and the neutral and earth is connected to the relevant neutral and earth terminals within the consumer unit (in accordance with the manufacturers guidelines).

As we have commented, this will need to be done by a qualified electrician. Before any work is carried out the electrician will isolate the entire consumer unit by turning off the mains switch and also probably the RCD, if there is one, for the bank that the MCB is being installed on, just to be doubly safe.

16amp MCB for new radial circuit

Step 2 – Connect Cable to MCB

The next job is to connect the cable to the MCB once it’s installed. The mains and RCD for the consumer unit should still be turned off, however the MCB should be turned off also.

Before anything is connected up the cable is run out to the location of the first socket. If it’s being surface fixed ensure you route it around any corners and leave enough slack. Where each socket is going to go, make a 6 inch loop in the cable and then continue to the next socket location and repeat.

If being run through a cavity behind the face of an OSB or plasterboard stud wall, drill an small 25mm hole at the location where the socket will be installed, route the cable around to the hole and then pull a 6 inch or so loop through the hole.

The loop in the cable can then be cut at the top and this will form the first run of cable for the first socket and then the next length of cable that will run to the second socket

The cable after the loop is then run to the next socket point and the same process is followed in terms of creating a loop to run to the next socket.

When the final socket in the circuit is reached, the remaining wire is pulled through.

Cables loooped through hole ready for socket

Step 3 – Wire up Sockets

The next job is to then wire up each socket face-plate to the cable pulled through each hole in the wall or at each loop is surface fixing.

Starting at the first socket, cut the loop in the cable in half so that there is now two individual cables, one from the consumer unit to the socket and one that runs to the next socket.

Wiring up a socket is similar to wiring up a plug in that each individual wire in the cable needs to be connected to its respective terminal; Live wire to live terminal, Neutral wire to neutral and earth to earth.

Firstly, lay the cable over the back of the face plate and get an idea of how much sheath needs to be stripped from the cable and then mark the sheath, score with a sharp blade, ensuring you don’t touch the wires inside and then run the knife down the very centre of the sheath, prise it open and then strip it back.

Cable sheath stripped back

Next strip off roughly 10 – 12mm of sheath from the end of each individual wire for both cables and then twist up the individual strands and then fold them in half so the end touches the sheathing.

Individual wires stripped back, twisted up and bent over

The final job now is to connect each wire to its relevant terminal; live wire to live terminal, neutral to neutral terminal and earth to earth. Remember to put each relevant wire from both cables into each terminal.

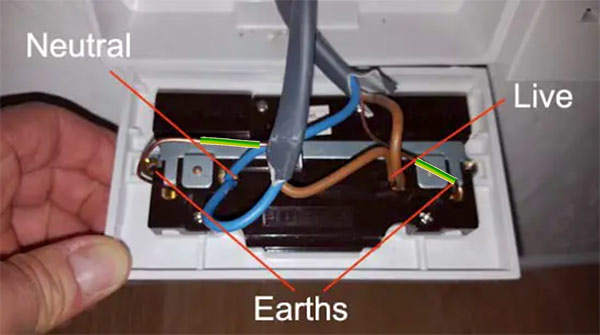

Wires connected to rear of socket face plate

Step 4 – Wire up Remaining Sockets

The first socket had now been successfully wired up. The next job is to repeat the above process for the rest of the sockets until the final socket point is reached.

The connection of the final socket in a radial circuit is exactly the same as the others e.g. you strip the cables and wires and then connect them to the correct terminals, only this time there’s only one set of wires to be connected up.

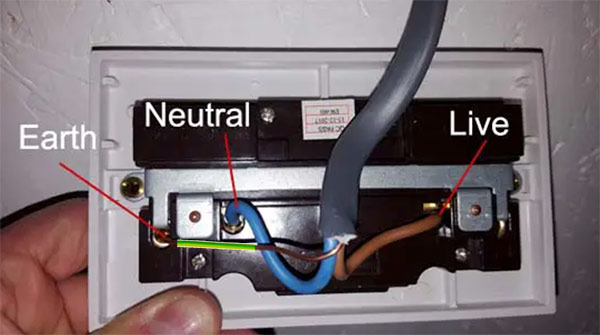

Final socket in radial circuit wired up

Note: Ensure that you add some earth sleeve to any bare earth wires to signify that each is an earth as stated by the regulations.

Step 5 – Test Circuit

Once all sockets have been wired up correctly, a full and complex series of tests must be carried out to ensure all is working as it should, and there are no faults.

This must be done by a competent and registered electrician and an appropriate certificate issued. This certificate and all the data contained in it, is your assurance as a DIYer that your work is safe and complies with BS7671 IET Wiring Regulations and Part P of the Building Regulations.

This is something that your are obliged to ensure if you carry out electrical work on your own home.

Once the test has been done and all is well, you’re now free to use your new sockets.

Wiring in a new radial circuit is a fairly straightforward job if you are competent and have a good understanding of electrics, but if not, you should feel no shame in getting the professionals in.

You must also ensure that all electrical work that has to be carried out by an electrician is done so and not by yourself as this can invalidate your home insurance if anything goes wrong.