Learning how to lay your own bricks and blocks is a very useful skill to poses and one that you will find that you use often.

In this project we cover how to lay bricks and blocks correctly and for ease of reading we have broken this down into the following topics, and if you want to skip to the relevant section, just use the links below:

- Cavity Walls – Simple guidance for building cavity walls

- Types of Brick – A quick guide to the types of bricks that you could use and how they might affect your build

- Types of Brick and Blockwork Bond – This explains the difference ways that you can place the bricks or blocks to build your wall, and the benefits of each option

- Types of Block – Here we explain the differences between the various types of block commonly used and some tips for laying them

- How to Lay Bricks and Blocks – This is how you actual get around to the business of building your wall by laying the bricks or blocks

The Importance of a Good Foundation

Before you can start your build you first have to lay a suitable foundation. How well this is done will ultimately determine how long your bricks and blocks, once laid, actually stay upright.

There are several different types of foundation that should be used for different purposes and to make sure that you are using the correct one for the bricks or blocks you are laying, please view our Foundations Project and follow the guidelines.

When laying a foundation for brick or block work you need to ensure that, firstly, the trench that it’s laid in is totally smooth along its base so that the foundation is of a uniform thickness all the way through. If not then this can create weak spots where it can crack and fail.

When a foundation is poured you should also ensure that it is as level as possible across its entire area. This will help to make laying your bricks or blocks easier and also help ensure that all courses are level with each other, however many that may be.

Foundation laid ready for block work to be laid

The Rules for Building Cavity Walls and Key Things to Look Out For

If you are new to wall construction then you may not be familiar with what a cavity wall is. Essentially there are 2 types of walls, the solid wall where the wall itself is one solid section and the cavity wall. With the cavity wall, 2 different walls are constructed, an inner leaf and outer leaf and between these 2 there is a void or cavity that varies in width depending on the type of wall being built.

Most wall construction today uses the cavity method as it prevents many of the issues associated with solid walls and also allows for the installation of modern insulation in the cavity.

- The actual construction of a cavity wall can vary, but in all cases (Building Regulations Approved Document A) the leaves of a cavity wall must be a minimum of 90mm thick with a minimum 50mm cavity in between

- The two skins of a cavity wall are held together by wall ties built into the mortar bed of the bricks and blocks. If the cavity is between 50 and 75mm wide the ties should be placed at a maximum spacing of 900mm horizontally and 450mm vertically. If the cavity is between 76 and 100mm wide the ties should be positioned at maximum intervals of 750mm horizontally and 450mm vertically

- All wall ties should always slope towards the outer skin very slightly to stop any moisture in the cavity being able to travel towards the inner wall

- The wall ties are often used to hold sheets on cavity insulation in place and the type and thickness of this insulation will be dictated by the Building Control officer

- The cavity, in a cavity wall, is there to prevent moisture from traveling from the outside skin to the inside skin. The cavity also, in almost all cases, is used to insulate the internal wall against heat loss from inside

- It is important when building cavity walls to keep the cavity free from debris at all times. Even a dropped trowel of mortar can collect on a wall tie and transfer moisture and cold temperatures across the cavity (more on this below)

You may also find our Cavity Walls Project useful if you want to learn more about cavity walls.

Cavity Walls and Damp Issues

We have had many questions over the years about damp and cold spots on walls in an otherwise warm room. This is usually the result of a transfer of cold temperature from the outside wall to the inside via what is known as a bridged cavity.

This can be particularly noticeable at the sides of window and doors (reveals) where the cavity is closed to allow the fixing of the frame.

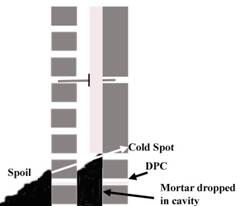

Cavity Wall Cross Section Side View

Cavity Wall Cross Section Top View

The top diagram above shows what can happen when two very common things occur during the construction of a cavity wall. First a lump of mortar has fallen from the trowel into the cavity.

When this goes unnoticed, a few things happen:

- Any insulation that has been added to the cavity cannot be pushed all the way down to the required DPC level

- The mortar has bridged the cavity allowing moisture and cold temperatures to pass between the skins of both cavity wall to the inside room space

At the same time as both of the above occurring, while the garden was being dug over, a heap of spoil was left against the wall. The top of the heap is above the height of the DPC creating a bridge around it.

As a consequence of these two very regular occurrences, ground water can rise up into the soil heap which is probably already damp anyway.

This moisture can soak into the brickwork above the DPC and, via the mortar in the cavity, soak into the internal wall. This makes a section of the internal wall cold and even damp allowing the warm air in the room to condense in this “cold spot”.

Because the wall is covered by very porous plaster this damp cold spot can be home to any number of mould spores which will soon show as a dark mouldy patch which, no matter how hard you scrub, will not go away.

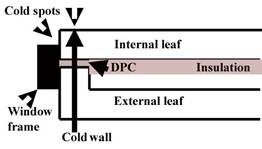

The second diagram above shows, looking from above, how a cavity wall is returned to close the cavity when meeting a door or window opening.

It is at this point that there is least insulation present and cold temperatures can also travel through the walls creating cold spots and ultimately condensation and mould.

A vertical DPC inserted between the two walls will stop any damp from getting in, but the cold spot inside can still lead to condensation forming on the wall. Read all about how to use a vertical DPC here and how they work.

General Rules for Wall Construction

After looking at some of the specific issues surrounding walls and their construction, it’s time to take a quick look at some of the more general rules:

- Plans must be checked carefully to ensure any openings, windows, doors etc. are even and level across both horizontal and vertical axis

- Regularly check diagonal measurements when building walls to ensure they are accurate to plans

- Constantly check everything is square

- Construct both leaves of a cavity wall at the same time to ensure everything is square and level and that each leaf supports the other

- To avoid any stressing issues, make sure you don’t build any higher than 1.5m in a single day, before everything has had time to cure. This is roughly 16 courses

- When laying bricks or blocks, use a standard bond and around a 10mm bed of mortar

- If using bricks with “frogs”, ensure the frog is facing upwards

- Ensure all cross joints are fully filled

- Ensure all bonds are fully filled

- make sure the cavity is kept fully clear, this includes any dropped mortar

- Wall ties should be set into the mortar bed by at least 50mm

By keeping all of the above guidelines in mind when constructing your walls will ensure that once you are done they are sturdy and strong, all openings are even and everything is nice and square.

Types of Brick and how They are Made

Aside from the rules governing how bricks and blocks should be laid for a successful outcome, it’s also important to understand the actual materials you’re using and when certain types, especially bricks, should be used.

Most bricks are made from clay. This type of clay is imaginatively titled, Brick Clay. Clay bricks (and tiles) are very durable and extremely versatile.

In days gone by when bricks were shaped and fired by hand in small batches, different coloured clays, of different compositions, from different areas were used and due to this brickwork was as much of a visual delight as it was practical.

With the increasing demand for housing, larger and larger automated factories were developed to produce bricks on a mass scale and also ensure that they were all of a uniform size. These bricks became known as “standard bricks”.

Despite this, special bricks (hand made etc.) are still available today although they can be quite costly and experimentation with different clays (normally associated with the special brick making process) is advancing brick technology to keep up with the demands for increased durability standards.

Architects and Planners these days are interested in re-developing properties (and other) buildings using techniques and appearances which are sympathetic to existing local styles.

In the 30 years between 1974 and 2004 it dropped from 5,000 million to 2,750 million, just over half and in 2008, due to the recession dropped to an all time low due to the fact that many factories closed down.

This huge drop in the production of clay bricks is accounted for by the huge rise in concrete products used today together with a massive increase in timber and plasterboard internal wall construction.

However, when the housing market picked up again around 2015 we then had to start importing bricks and by 2019 the UK was the largest importer of bricks in the world, but despite this by 2021 brick stocks were at an all-time low.

To counter act this and our reliance on imports 3 brand new brick production factories are due to start production sometime between 2023 and 2024 and jointly should output around 150 million together. This should go some way into plugging the gap.

Common Bricks

The term “common brick” comes from the fact that, although they are fired hard enough to use for most brickwork load-bearing operations they are of a lower quality than facing, or engineering bricks. No attempt is made to control their colour and their composition is such that they should not be used below ground.

They are used mostly for indoor partitions and for parts (or skins) of walls that will not be seen. They are lighter in weight than facing and engineering bricks. Their use is, as described above, being overtaken somewhat by the use of concrete and lightweight blocks for internal partitions.

Common bricks

Engineering Bricks

An engineering brick goes through a more elaborate process of clay selection, careful crushing, firing and moulding to make it a very hard brick indeed. The process delivers a brick which is has very high compressive strength with very low water absorption.

Engineering bricks can be used underground and are often laid as a damp proof course. They are rated in two classes, A and B with A being the strongest and least absorbent. This type of brick is used in situations requiring the strongest of work.

Engineering brick

Facing Bricks

There is a number of different types of facing brick but generally they are the “face” of the building.

They are hard burned to give them strength and durability which they need to withstand the hugely varying temperatures and climate available in the UK, not to mention the acid attack from smoke and soot from any number of industrial locations and cars.

Facing brick

Stock Facings Bricks

Stock Facings, or stocks, are a soft, irregular facing brick produced by pressing wet clay into sanded moulds. It is by using sand to release the stocks from the mould that gives them their soft texture and slightly irregular shape.

Stock facing brick

Wirecut Bricks

Most facing bricks in the UK are shaped by wire cutting. The tightly packed clay is pushed through a die where it gets its perfectly rectangular shape. The face is then added. The block or column of faced clay is then wire cut into individual bricks and fired in a kiln.

Wire cut brick

Waterstruck Bricks

Waterstruck bricks are released from the mould by water. They contain no holes or frogs and have smoother edges.

Water struck bricks

Handmade Bricks

As you would imagine, these bricks are hand-made. An extremely expensive process which, as the clay is folded into the moulds, produces distinctive creases (smiles) in the brick. Handmade bricks are used in the most prestigious of buildings.

Hand made brick

Reclaimed Bricks

Another brick that does exactly what it says on the tin. Reclaimed bricks can be a variety and mixture of the above facings.

The fact that they have been used once and reclaimed gives them creases and marks which will add something to any building they are used on.

Because reclaimed bricks tend to come from older buildings they are often in imperial, rather than metric sizes. This makes it difficult to integrate them into larger, modern walls, so special reclaimed “panels” are often inserted.

Reclaimed bricks

Special Bricks

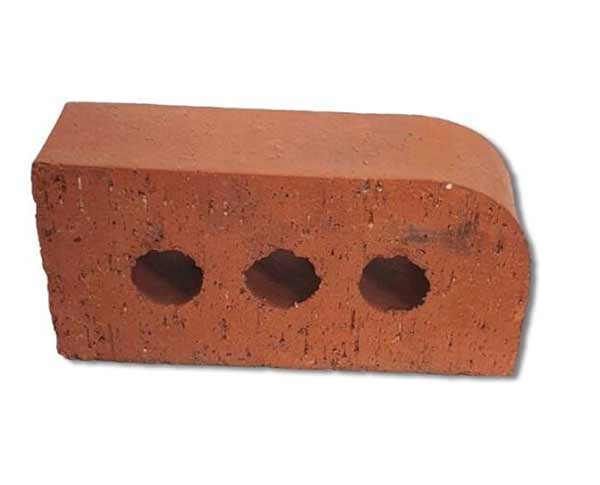

Special bricks are so called because they are made to fulfil a specific task. An example of a special is a bull nosed brick shown in the image below. This type of brick is used to finish off the top of a wall or even as a window sill.

Other often used specials include plinth bricks, copings, arch keystones and many others. Brick companies can make a brick into almost any shape you like as long as you are prepared to pay for it.

Bull nosed special brick

All bricks have different uses but all need to withstand a certain amount of wear and tear.

To test them, bricks are crush tested to determine their usability and the crush testing result for each brick type is an average figure based on the crushing of twelve bricks of that type.

Crushing strength is measured in Newtons per mm square and the softer of facing bricks will have a crushing strength of about 3 – 4 N per mm square whereas engineering bricks will not fail until approximately 145 N per mm square.

Types of Brickwork and Blockwork Bonds

As different bricks are used for different conditions, and in different walls, so different ways of laying them are employed in different situations.

Some walls are laid so you can only see the ends of the bricks, some in a way which only leaves the sides visible. These different ways of laying bricks are called “Bonds” and the most popular are listed below.

However it is done it is imperative that the maximum strength possible for the task of the wall is obtained.

Some popular bonds are shown below together with an explanation of where they are most likely to be used.

Brickwork or blockwork bonding should be laid out dry before you start to make sure the bond works. Sometimes bricks should overlap the brick below it by half of its length (half bond).

Some brickwork types use a quarter bond where one brick overlaps another by a quarter of the width of a full brick.

Believe it or not buying a pack of dominoes for a few pounds, and practicing brickwork bonds with them can save you a great deal of time and money when it comes to building a retaining wall in the garden or any other similar brick or block laying job.

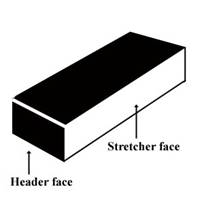

What are the Different Types of Brick Face?

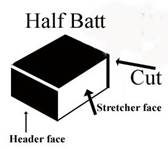

The Different Faces of a Brick

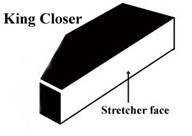

Before we go into the various different types of brick bonds, it’s important to firstly look at the different faces of a brick so that when we refer to the “stretcher face” or the “header end” you know which side face of a given brick type we are referring to.

The long face that you can see in a brick wall is called the Stretcher face. The shorter “ends” are called Headers.

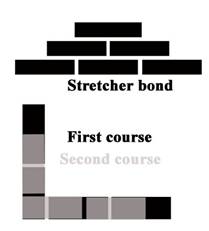

Stretcher Bond

Stretcher bond is the most commonly used in house construction in the UK because it allows for the most economic use of bricks and also the speed in which this bond can be laid in most construction situations as it only require a single width (half brick) skin.

Two stretcher walls can be built back to back and tied together using wall ties to form a double (single brick) cavity skin.

The type of tying method used is called a collar tie. This allows for an attractive face on both sides of the wall but it’s not the strongest method of producing a single brick wall as the ties between the skins are a weak point.

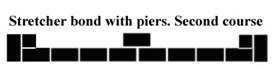

Stretcher Bond, First Course and Second Course

Stretcher bond uses 60 bricks per square metre in a half-brick, or single skin wall. This is obviously doubled to construct a double skin, or One-brick wall.

You can see clearly in the diagrams how each brick in the stretcher bond overlaps the one below it by half of its length. Turning corners with stretcher bond is simply a matter of placing one brick at right angles to another. This automatically continues the half bond.

To finish off the ends of the wall, a brick is split in half (half batt) and laid to keep the end of the wall in line vertically.

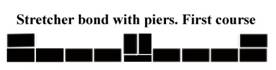

Strengthening Long Walls

As said above, Stretcher bond is not the strongest of bonds and if a wall of any length is built, piers must be inserted as set points along its length to maintain strength.

First Course Of Bricks Laid

Second course of bricks laid

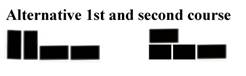

Alternative First and Second Course

There are two ways to end a stretcher wall with piers. The middle directly above shows the use of a half-batt in alternate courses while the bottom image shows the use of a three-quarter batt.

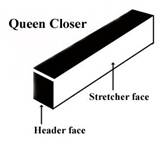

Dealing With Gaps – Using Closers

In some brickwork bonds a gap develops which is not the same size as a full or half brick. In these cases a brick is cut to fit the gap and this cut brick is called a closer.

Some bonds do not work at all without closer’s and the same size/type of closer is used in every (or every other) course.

Where the closer has common usage it is often named. Some common naming’s are “King” or “Queen” closer’s. Additionally, half and three-quarter batts are quite often used.

Half Butt

Queen Closer

King Closer

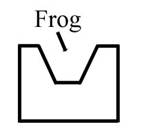

What is a Frog?

Most bricks used for home construction in the UK have indents in the top of the brick. This indent is called a frog and if bricks are laid to British Standards, as they should be, the frog should be laid upwards and filled with mortar.

Frog that features in the top of some bricks

British Standard Code of Practice BS 5628-3 states:

Unless otherwise advised, lay single frog bricks with frog uppermost and double frogged with deeper frog uppermost. Fill all frogs with mortar. This maximises strength, stability and general performance of the brickwork.

Frog laid upwards correctly and filled with mortar

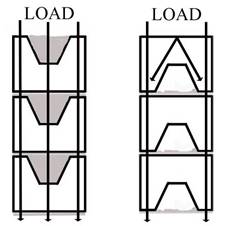

When the frog is laid upwards, the load is evenly spread throughout the width of the brick all the way down to the foundations. If the frog is laid down, the load is forced to the outsides of the brick.

As stated already, the most common bond used today is Stretcher Bond and for DIY purposes this is a perfectly adequate bond especially for use in the garden.

Again as we have discussed, the problem with single skin Stretcher Bond is that it has very little strength when pushed from back or front. Despite this is it often used as a retaining wall and more often that not will buckle and fall over under the pressure of soil.

Our garden wall retaining project is about building a garden wall and shows you how to lay bricks or blocks for this type of job.

Now that we have looked at the stretcher bond, it’s time to take a look at some other bond-types:

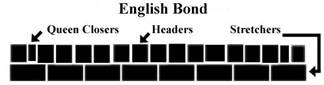

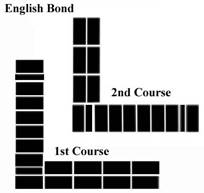

English Bond

English bond (also known as Ancient Bond) requires quarter bond work in its construction of a course of stretcher bricks and a course of header bricks laid alternately.

English Bond

This type of bond is the strongest brickwork bond. It is however, one of the most expensive because of the labour time and volume of bricks used.

The Victorians, when building many of their classical gardens, introduced a variation on English Bond, called English Garden Wall Bond which introduces the course of headers in between five courses of stretchers.

This maintains the strength, looks attractive and is cheaper and quicker to build.

It can be seen from the image below that English bond requires closures on each course to maintain the bond. This type of closure, a brick cut down the middle of its length, is, as we have stated above, called a Queen Closer.

First and second brick course of an English bond brick wall

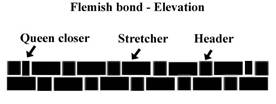

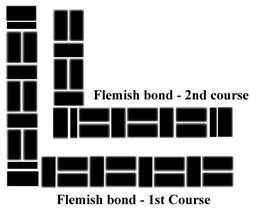

Flemish Bond

Not quite as strong as English Bond but used for it’s visual effects, Flemish Bond is laid using stretchers and headers alternately in each course to give it a quarter bond finish.

Flemish Bond also has a “garden wall” variant in so much as the number of stretchers in between the headers can be increased.

Flemish Bond – Elevation

Flemish Bond first and second course

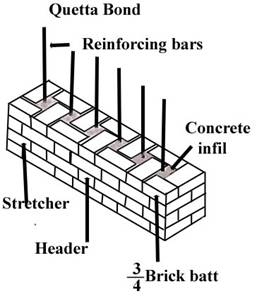

Quetta Bond

Quetta Bond is a brickwork bond designed specifically for the Industrial use of retaining and load-bearing support. This bond can be easily adapted for garden use where a very strong, attractive retaining wall is needed.

Quetta Bond

The wall is built as shown in the image above using stretchers and headers and the voids created by this bond are filled with concrete. The first course of this type of wall is built laying the bricks onto the concrete foundation before it has set.

Steel reinforcing rods are driven into the concrete foundation, through the voids and further courses built up around these rods. When the voids are filled you are left with a very attractive, very strong garden wall which will retain pretty much anything you throw at it!

The steel reinforcing bars (12mm High Tensile bars are recommended) can be bought at any builders merchants and easily cut with a hack saw or angle grinder.

Honeycomb Bond

This bond is used for decoration in garden walls as shown but serves the useful purposes of allowing some visibility and also creates less resistance to strong winds.

Honeycomb Bond

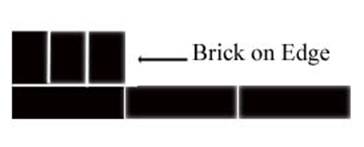

To finish the top of a wall, a course of bricks is often laid on one of their stretcher edges. This is called, again inventively, a Brick On Edge course.

Finishing layer on Honeycomb bond wall

Additional Finishing Techniques

Another way of finishing a garden wall is by using coping stones. Coping stones are cast with an angled top to allow the water to run off and, as with window sills, usually overhang the brickwork slightly so the water does not run down the face of the brickwork and stain it.

Coping Stones used to cap-off and finish a garden wall

Additional Strengthening Techniques

For extra strength with any type of wall, a galvanised steel mesh can be laid into the mortar course. A little like chicken wire, this mesh is called Expanded Metal Lathing and is available from Builders Merchants in sheets and in rolls.

For the DIY enthusiast it is far more useful in rolls which come in various widths ranging from 50mm to 450mm. The mesh can be cut with a hacksaw or better still, tin snips, and can virtually double the strength of some walls.

Different Types of Blocks and Blockwork

Concrete and lightweight blocks are widely used in all areas of building and DIY. They can be bought with a “Fair face” for work which will be visibly seen.

They are much quicker to lay given that 1 standard block is equivalent to 6 bricks. For purchasing purposes there are 10 blocks to the square meter when the block is 440mm x 215mm.

These dimensions are the same as two bricks and 1 mortar joint wide, by 3 bricks and three mortar joints high. This allows blocks and bricks to be used (and bonded) together in a simple way.

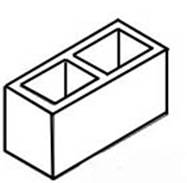

Standard concrete pillar block or hollow block

Concrete Blocks

Blocks come in various thicknesses. Typically most standard UK concrete blocks are around 100mm thick. This is true for both the heavier solid concrete blocks and also the lighter Thermalise blocks.

When it comes to laying blocks, they can be laid flat. Walls built using flat blockwork in a Stretcher Bond style are incredibly strong.

Special blocks are used for various applications and one of the most common of these is the “Hollow” block (as seen in the image above). The hollow block can be laid as it is and the voids used for insulating purposes, or the voids can be filled with concrete to make a very strong and solid wall.

Concrete blocks are almost always used in foundation walls as they are so much cheaper in terms of labour time to lay.

A word of warning to the DIY bricklayer here. Concrete, or any other blocks, are not easier to lay than bricks. Getting a block level, on a flat level mortar bed is every bit as difficult, if not more so, than laying a brick.

Bricks can be picked up and lightly pushed into a bed of mortar with ease. A block however may take some “persuading” with a hammer or the handle of the trowel (not recommended). Because of its surface area, hitting a block in one place will make it move in another and then the block will start to rock.

Because of their weight, hitting a block will cause the one underneath (if you are more than 1 course up) to move also and laying a block wall, even though the blocks are heavy and cumbersome, requires a light touch. We would not recommend laying more than 5 courses of blocks in one go.

Standard solid concrete block

Lightweight Blocks (Thermalite Blocks)

Lightweight blocks can be used in conjunction with all types of building. The blocks have all of the qualities needed to satisfy the Building Regulations both inside and outside, load bearing and non load bearing.

The strength of lightweight blocks in very deceptive and their compressive strength, needed to form the load bearing inner skin of a cavity wall, is far more than is required. The lightweight nature of the blocks allows them to be picked up and laid with one hand, a huge bonus when you are laying blocks and your back will thank you for using them at the end of a long day.

Thermal resistance ( U ) values are met much more easily with lightweight blocks and their ability to deaden sound makes them perfect for modern domestic internal use. The thermal resistance qualities alone can save a great deal of money on other insulation.

Cutting lightweight blocks could not be easier. They can be cut to any shape or size using an ordinary carpenters saw. Do yourself a favour though and don’t actually borrow the carpenters saw to do it, he won’t be happy!

Lightweight blocks can be drilled as easily as wood and the only real problem is getting a strong fix to them for shelves, cupboards etc. However special light-weight fixing plugs can be bought from Builders Merchants which are literally screwed into the blocks and then normal screws fixed inside those.

Lightweight blocks are considered to be non-combustible giving them a great rating in the fire resistance section of the Building Regulations.

Their ability to withstand sulphate attack allows them suitability in the ground and their resistance to frost has been proven time and time again.

Freeze-Thaw action has already been mentioned in the preceding chapters (and more can be found in our freeze-thaw project here) and lightweight block have shown no tendency to lose compressive strength under the conditions associated with freeze-thaw.

Lightweight blocks have millions of tiny air pockets in their structure but these are not connected making them able to withstand damp conditions well.

Standard Thermalite light weight block

Glass Blocks

Glass blocks are now widely used. These can be laid as normal blocks, i.e. with sand and cement joints, or by using special frames and spacers which usually come in kit form with the blocks.

If laying glass blocks with sand and cement, it is as well to remember that glass has no porosity at all and if care is not taken a wet mortar mix will very soon squeeze out all over the face of the blocks.

Glass blocks can be laid indoors or out and are an excellent way of letting light into a space while still keeping that space separate from others. They come in a variety of sizes with a clear or frosted finish for maximum privacy.

Glass blocks are tested to see how long it takes before fire makes them unstable and they are also tested for their thermal insulation qualities. This, if the correct block is chosen, will keep them within Building Regulation guidelines.

Glass building block

Tools and Products Needed for Laying Bricks and Blocks

In order to lay bricks and blocks correctly, the following tools and products are required.

- Bucket trowel

- Pointing trowel

- Brick laying trowel

- Sand

- Cement

- Cement mixer, spot board or wheel barrow for mixing cement/mortar

- Spirit level

- Boat level

- Enough bricks or blocks for the job

- Ballast (for making foundations, if needed)

- Brick line

- Pen/pencil

- Timber batten for marking height

- Scaffold if working at heights

How to Lay Bricks and Blocks

Now that you have learnt all about the different types of bricks and blocks, the types of bonds and how different bricks or blocks should be used, it’s time to look at how to actually lay them.

The bond that you choose to build your wall with is up to you (unless there are any Building Control stipulations) but it’s a good idea to practice your brickwork before you start a major project.

Many of the frequently used brickwork bonds can be seen in the sections above. When it comes to actually laying bricks or blocks, the same technique is employed whatever you are laying and there are a few important things to remember.

If the last brick you laid is not level, do not bash it with a trowel, hammer or anything else. It may be that while you have bashed that particular brick into position, you have knocked several others out. However “robust” a brick wall appears, while it’s wet it can move all over the place if not handled properly. As we have mentioned, this is especially true of heavy blocks.

Step 1 – Laying a Foundation

To ensure that a wall stays upright and intact for a good length of time it is essential that it is laid on top of the correct type of foundation.

There are several different types of foundation and the one that you use will very much depend on the type of wall that’s being built. For example, the foundation depth and strength for a house wall is quite different to the one used for a conservatory.

To find out exactly what type of foundation you need to use see our foundations projects here.

Step 2 – Getting the Correct Mortar Mix

The mortar that you use will depend on a number of things including the type of wall you are laying. This is a whole project in its own right, so have a read out our project all about mixing mortar to ensure that you get the right mix.

We also cover how to mix up the mortar on a spot board or in a wheel barrow. See all about how to mix mortar here.

Step 3 – Before you Start Laying Bricks or Blocks

Once the foundation has been laid and left for a good few days to fully cure and you have mixed up the correct type of mortar mix, lay a bed of mortar on top of the foundation ready for your first course.

If your bed of mortar is the correct depth and the mix is pliable enough, level it to a uniform thickness, roughly 10mm and you should be able to place the bricks down gently and with a gentle twisting motion, get them into the correct, level position.

Ensure that as you lay each brick that you add mortar to each end so that it butts up to the last brick or block.

Now and again a gentle tap is required with the handle of a trowel, but after this tap a bricklayer will always stand back to make sure nothing else has moved.

If time and care are taken over the first few courses the rest of it gets easier. If the first few courses are not level in any way, it becomes a really hard job to get a nice finish.

Getting the Right Height

To make sure your wall finishes at the right height, get a timber batten the same length as the proposed height of the wall to be built.

On the batten, mark in pencil each course of bricks or blocks (These marks will need to be adjusted so you will need to remove them before you make your final marks). Start at the bottom of the batten and work your way up.

See where the last mark comes to on the batten and measure from there, to the end of the batten. In some cases, if this gap is not huge then you increase the depth of the mortar in each bed joint slightly (Note: a bed joint should be no more than 15mm) or if it is easier to add another full course, the bed joints can be made a little thinner. We would not recommend laying a joint of less than 6mm.

Check the level of your blocks

Check Levels Regularly as you Lay

As you build the wall check not only the line, level and how upright the wall is. Check the level across the width of the wall. Bricks and blocks can show level along their length. They can show, by looking at the spirit level to be perfectly upright both from the front and from the side. Then you stand back and take a look and the job is dreadful.

This is normally always because the wall is not level across its width. The bricks tilt one way and then the other but at least one part of the brick is touching the spirit level so the wall appears to be correct.

After a few years you get the hang of “feeling them down” but until then the spirit level, in all directions, is the best friend you have. It may seem a little over the top, but if you do lay any yourself, you will see it is not!

In the sequence of images showing the laying technique below, you will see a small “boat” level across the wall. This is carried just to make sure of a perfect level across the wall.

Step 4 – Start Laying Your Bricks or Blocks

To begin laying, place some of your mortar mix on a “spotboard” close to the wall. Use your trowel to roll the mortar down the heap until it forms a sausage at the bottom. Slide the trowel under the sausage and then let it slide off again into position on the foundation for the first course of bricks.

Use the point of your trowel to form a “V” in the mortar bed. If you have seen our project on laying ceramic tiles you will know that this “V” allows for displacement of mortar as you push the brick down. Once again the same principle is applied to many jobs.

Use the point of your trowel to form a “V” in the mortar bed

Place your bricks carefully, but firmly onto the bed. Push down with a slight twisting movement leaving a bed of 10mm under the brick. Place the spirit level at the back (or front) of the bricks to check they are being laid in a straight line.

As we have said, make sure you fill the joints between the bricks by adding some mortar to the end of the brick or block before it’s laid.

Place the bricks carefully down on the mortar bed

These bricks are being laid to stretcher bond and once two or three courses are built its time to check for plumb on the end. Do this on every course.

Bricks laid to Stretcher Bond

The wall needs to be checked every course for plumb at the front and at both ends, on every course. The horizontal level of the bricks or blocks can be checked using a small boat level. If the wall starts right, it should end right!

Check the bricks or blocks for their level every course

Step 5 – Build up Corners

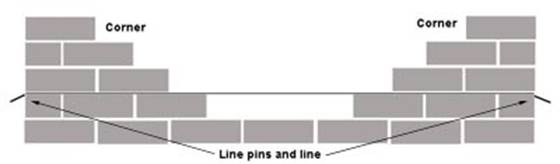

The first course is laid throughout the length of the wall, but instead of building up in further layers, the ends are built up first to about 5 courses at either end. These ends then become known as “corners”.

When the corners are up they are used as a template for the rest of the wall by stretching a string line (also known as bricklayers lines, or line pins).

The pins are pushed into the mortar joints and the string stretched between them.

The bricks that form the rest of the course are then laid so the top edge of each brick is touching the line. If your corners have been built properly, constructing the rest of the wall should be easy.

Do not use a line for a wall that is over 6m long as it will sag in the middle. For walls this long you need to build another “corner” in the centre of the wall.

For walls over 6m long, build another Corner

Step 6 – Use Scaffold When Walls get too High

At some point your wall might get to a height where you need a scaffold or a scaffold tower. If this is the case, please be careful as this is where most accidents in construction occur. See here for information about working at height and on scaffolds safely.

This project should have given you a comprehensive overview to all the most common aspects when it comes to how to lay bricks and blocks.

To build a brick or block wall is something that takes a little practice but it something that makes an excellent DIY project. With the right types of brick and block, and using the right mortar and brick bond there is no reason that you cannot make a fine looking wall yourself!